Imaginary dialogue based on my reading of the Prisoners of Shangri-La by D. Lopez and Who Are the Prisoners? by Tsering Shakya

My goal is to clarify for myself and for my readers if Tibet’s collective conception of its national identity is shaped by the Western influence (Pr. Lopez) or stays unique and independent from the Western alteration (Pr. Shakya). Has the West, in fact, made any impact on Tibet, or is Tibet purely an example of an Eastern religion being co-opted, assimilated and misunderstood in the West?

In order to distill the essence of this debate, I will juxtapose the two controversial views represented by Tsering Shakya and Donald Lopez and comment on them.

Please keep in mind that this dialogue has never taken place in the real life.

Tsering Shakya Donald Lopez

Tsering Shakya is a Canada Research Chair in Religion and Contemporary Society in Asia, Institute of Asian Research, University of British Columbia

Donald Lopez is a Distinguished University Professor of Buddhist and Tibetan Studies, Department of Asian Languages and Cultures, University of Michigan

- Tsering Shakya: Who are the prisoners of this handsomely designed work Prisoners of Shangri-La?

Donald Lopez: The theme of imprisonment applies to the Tibetan people imprisoned by notions held by Westerners.

Comments: I believe that both Westerners and Tibetans are imprisoned in some way. In the Western-Tibetan discourse, the Western fascination with Tibet in sometimes bewildering ways has imprisoned Westerners, and the Tibetans have been imprisoned in the construction born of that fascination as well.

- Tsering Shakya: Perhaps, with regard to the current situation of Tibet the title could be better worded as Prisoners of China?

Donald Lopez: It might be the case if I wanted to concentrate on Chinese-Tibetan relations. But, this is not the main goal of the book. The Chinese question is only a fraction of where I was going to “recognize the case against the Chinese occupation and underscore the dangers of romanticizing Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism” (11).

Comments: In my view, Lopez’s intention is not fulfilled in the book, particularly in the chapter “Prisoners.” By emphasising the romantic Western approach, he belittles the real danger of Chinese occupation.

- Tsering Shakya: What is the meaning of being imprisoned?

Donald Lopez: It is mostly a mimicry, hybridization, and appropriation of the Western representation of Tibetans. Tibetans have become prisoners of the Western representation of Tibet.

Comments: This is essentially a romantic understanding of imprisonment that Lopez, consciously or unconsciously, carries throughout the book.

- Tsering Shakya: What are the forces that hold the Tibetan people imprisoned?

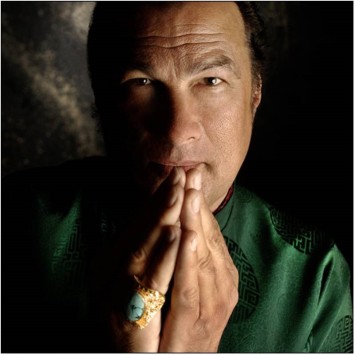

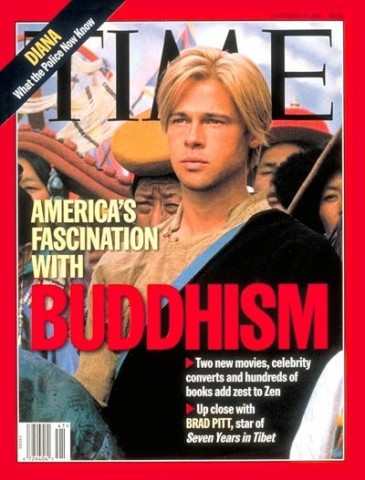

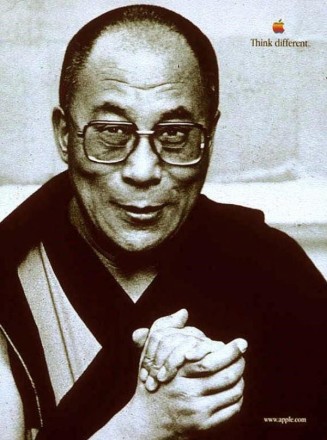

Donald Lopez: Western people fascinated with Tibet are holding the Tibetan people imprisoned. “I have become convinced that the continued idealization of Tibet—its history and its religion—may ultimately harm the cause of Tibetan independence.” (11) Those harming people are theosophists, fictional characters, artists, movie directors, translators, journalists, gurus. For instance, the Dalai Lama, Lama Govinda, Richard Gere, Steven Seagal, Blavatsky, Trungpa Rinpoche, Jeffrey Hopkins, Brad Pitt, Robert Thurman, etc.

Comments: Perhaps, those “dangerous” Western people are actually supporters of Tibet. Maybe the real forces of imprisonment are the Chinese colonists? And in reality, the Tibetan people are victims of their Chinese enemies and not their Western supporters.

- Tsering Shakya: What are the facts that prove that the Tibetans are altered by the Western representation of Tibet and Buddhism?

Donald Lopez: Tibetans in exile are utilizing popular Western political language which might be considered as alteration of the Tibetan belief system in general. Moreover, there is an increasing heightened popular interest in Tibet. For instance, Steven Seagal is named to be a reincarnated lama.

Brad Pitt from the popular film Seven Years in Tibet represents Buddhism on the cover of Time magazine.

Richard Gere is an active supporter of the political figure of the Free Tibet movement Dalai Lama.

Monks are participating in TV commercials playing basketball.

Based on these examples, the Western cultures seem to overpower the Tibetan one.

Comments: I wonder how much does the Western invention of Buddhism impinge on the Tibetans? If It has affected the Tibetan view of self, why are there no Western academic writings on Tibet that have been translated into Tibetan? How many Tibetans have received teachings from Western trulkus? I believe that there is a minor relationship between Western discourse on Tibet and Tibetan native subjectivity. The Western definitions of Tibet have not been so powerful that the Tibetans have been denied their agency, or have been colonized. Moreover, the Western Tibetan discourse has barely penetrated the Tibetan social world and is mostly addressed to the home audience in the West. It is possible that the Tibetan majority is not even conscious about the Western discourse on Tibet. On this note, Lopez’s work demonstrates the lack of attention to the words of actual Tibetans, particularly lay people. Ironically, he continues the tradition of Western scholars of Tibet who have overlooked the agency of ordinary Tibetans.

- Tsering Shakya: What are the sources of misinterpretation of Tibetan Buddhism in the West?

Donald Lopez: The sources of misinterpretation of Tibetan Buddhism in the West are psychological interpretations of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, The Third Eye by Englishman Cyril Hoskin, a tale of Tibetan spirit possession published in 1956, mistranslations of the famous mantra Om Mani Padme Hum, exhibitions of Tibetan art in Western museums, the institutionalization of the academic discipline of Tibetology, increasingly airy spiritualizations of Tibetan culture. Elements of Tibetan Buddhism become abstract symbols onto which Western writers project their own spiritual, psychological, or professional needs.

Comments: Om mani padme hum is recited by Tibetan Buddhists as “the jewel in the lotus.” Lopez discovered that this mistranslation has been used by everyone in the West: “based on the Tibetan sources and an analysis of the grammar, it appears that the mantra cannot mean “the jewel in the lotus” and that the endless variations on this misreading are merely fanciful” (p. 133). Lopez calls it “the ultimate irony” and proceeds to quote Trijang Rinpoche who derived his interpretation from the same mistaken Western sources. Here we can see how the author overemphasises the mistranslation of the mantra which, perhaps, should be discussed primarily in the endnotes.

- Tsering Shakya: It is an unexpected approach for you, Pr. Lopez, to focus on the Western romance of Tibet detaching yourself from being part of it. As an interpreter of interpreters, how do you find yourself functioning here twice removed from actual Tibet?

Donald Lopez: I think that “we are all prisoners of Shangri-La” (Introduction). I do not believe that Westerners might be prisoners of orientalist, modernist, and Chinese communist propaganda. For the most part, we are romanticizing Shangri-La and see Tibet as a perfect utopia, and not as a “backward, feudal, dirty, oppressed” country that needs cleansing and liberating.

Comments: Lopez is literally creating a subgenre within the academic study of Buddhism with a mission to critically assess the biases embedded in the views of the previous generations of scholars of Buddhist studies. Lopez fails to maintain his detached, ironic mode of looking at discourse merely as discourse (“Field,” “Prison”). He falls into a romantic mode that betrays his intent and suggests that the reader may trust Lopez to “more accurately depict what Tibet was ‘really like.’”

- Tsering Shakya: Let’s imagine that romanticizing of Tibet by the Westerners is a fact. Does it have positive or negative effect?

Donald Lopez: It has a negative effect because it shaped Tibet’s collective conception of their own national identity.

Comments: Perhaps, romanticizing Tibet might have a positive effect as it is helpful for freeing Tibetans from Chinese occupation.

- Tsering Shakya: Could you comment on the Dalai Lama example of a Tibetan in exile who is utilizing popular Western political language?

Donald Lopez: In the concluding chapter I mainly talk about the Dalai Lama’s exposure to the West and how it might contribute to my main argument on Western influence and the representation of Tibet in the West. Today, the Dalai Lama’s image is used to sell Apple computers, and his picture is on billboards; he is today perhaps one of the most widely-known religious figures in the world. There is an increasing demand for the Dalai Lama to speak and voice his opinions on a whole range of international issues. Therefore, today more than at any other period in history, the Dalai Lama is identified with Tibet, Tibetanness, and Buddhism.

Comments: There is no doubt that the Dalai Lama has been skilful in his campaign message to harmonize with fashionable trends in human rights issues, ecology, or spiritual values. But this change in emphasis does not entail a change in value system among the Tibetans. The Tibetan usage of the language of popular political rhetoric is a strategic calculation rather than a transformation of the Tibetan value system.

10. Tsering Shakya: What would be the consequences for a “more balanced Western view” of Tibet?

Donald Lopez: It would help “Tibetan independence” which is “harmed” by “idealization of Tibet—its history and religion.”

Comments: It would also apply that Tibet is only our imaginative construct and not a real place with real problems. It wouldn’t help in liberating Tibet from Chinese occupation either.

11. Tsering Shakya: If you could take sides in this book, which side would you take—Tibetan or Chinese?

Donald Lopez: Obviously, I would take the Tibetan side. The whole purpose of the book is to realize how unique and diverse the Tibetan culture and Tibetan people are. The Chinese are dangerous invaders.

Comments: Sometimes it is not very clear if Lopez is on the Tibetan site because of the contradictions between his intentions and his expressions. For instance, he intends to show “the case against the Chinese occupation” (11), but ironically falls into a romantic path and concentrates exclusively on the Western invasion.

12. Tsering Shakya: How would you evaluate the success of your book Prisoners of Shangri-La?

Donald Lopez: I believe that it has made an impact on a wide population and almost nobody who has read it could stay indifferent. This work is an unprecedented case where a Westerner was able to realize the danger for Tibetans in seemingly non-harming romantic obsession of Tibet.

Comments: In the case of achieving the goal of Tibetan independence, the book might have made a negative impact on such Western authorities as, for instance, M. Goldstein, who were actually supporting Tibet.

Used sources:

Lopez, Donald S. Jr. Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1998, pp. 275

Tsering Shakya. Who Are the Prisoners? Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol. 69, No. 1 (Mar., 2001), pp. 183-189

Thurman, Robert A.F. Critical Reflections on Donald S. Lopez Jr.’s “Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol. 69, No. 1 (Mar., 2001), pp. 191-201

That is a very good point, that Lopez may have excluded Tibetan agency in this consideration.

LikeLike

Hi Maria,

The imagined dialogue format is really apt – how did you decide to do it? I know it from Hind Swaraj; it seems really helpful for sorting through different angles and positions. The format you use actually brings up a new question – how do we imagine speaking for others? With your dialogue format, I tend to think that the characters would either need to be anonymous (as in HS) or well-known enough, as they are in the field, to be used to enact an imaginary exchange. Interestingly, the format sort of spurred me to keep coming up with my own points and make my own connections, as I was reading along, as though I could add another voice to the play.

LikeLike

What a creative post, Maria, I thought it was brilliant to set up an imaginary dialog between these thinkers, that would be a great format for a class discussion, perhaps a debate or something! The great thing is that the dialogic structure represents what we have been doing in class this year, so your structure captures that well

LikeLike